Table of Contents

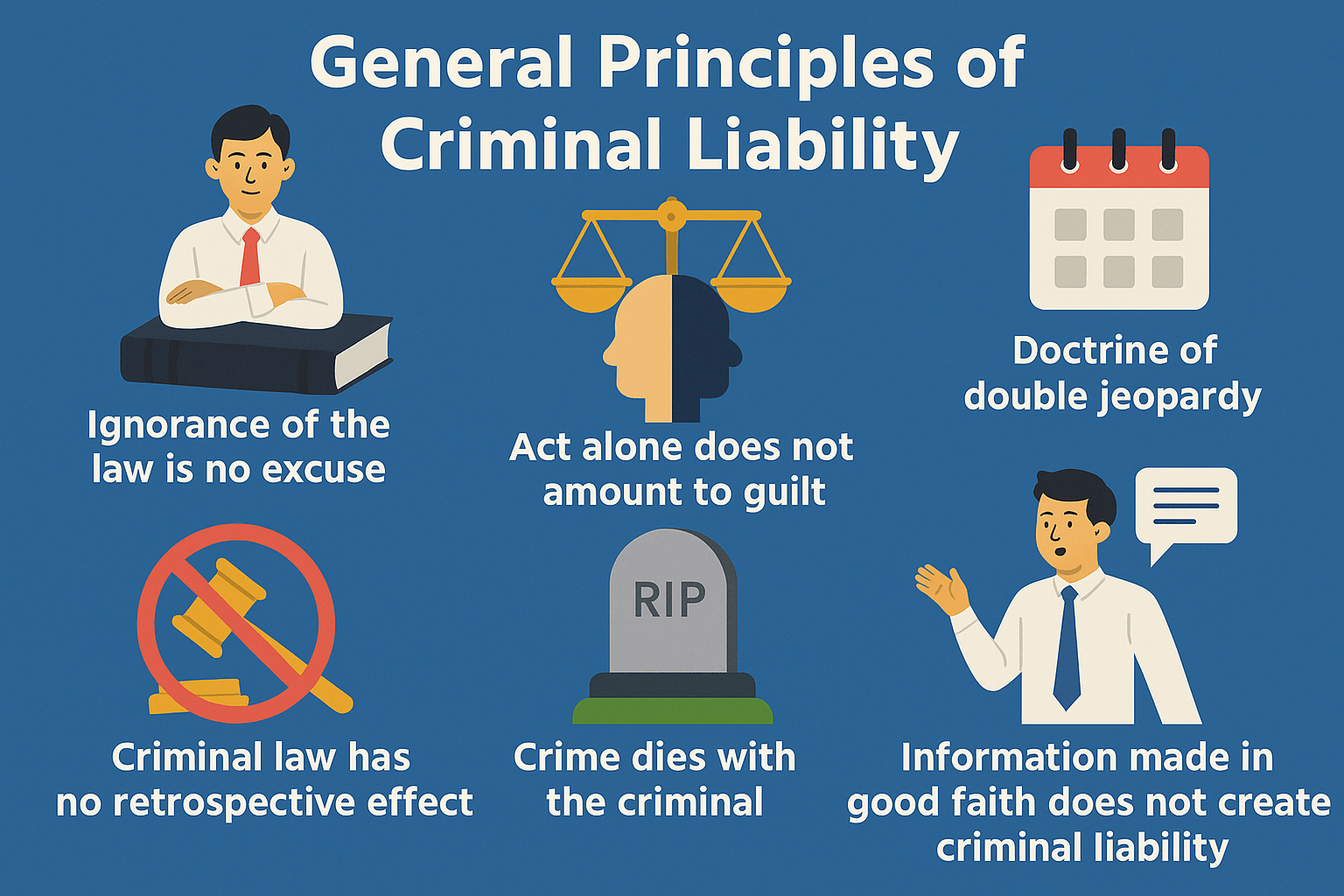

The general principles of criminal liability form the foundation of criminal law, ensuring fairness, accountability,and justice in legal proceedings. These principles define the essential elements required to establish criminal responsibility, including actus reus (the guilty act) and mens rea (the guilty mind). Key doctrines, including "ignorance of the law is no excuse," strict liability, double jeopardy, and the prohibition of retrospective punishment, safeguard individual rights while maintaining social order. Additionally, principles like "crime dies with the criminal" and good faith exemptions prevent unjust liability. Understanding these principles is essential for interpreting criminal laws and ensuring a fair and just legal system. General Principles of criminal liability are as follows:-

1. Ignorance of the law is no excuse

The principle "Ignorance of the law is no excuse" means that individuals are expected to know the laws that apply to them and cannot avoid liability or responsibility for their actions simply because they were unaware of the law. This principle is rooted in the idea that laws are established to maintain order and ensure fairness in society.

If a person commits an offense or violates a law, claiming ignorance of it will not absolve them from the consequences. The law assumes that people have to educate themselves about the legal system and abide by it, and if they fail to do so, they are still held accountable. Muluki Criminal Code 2074 Sec 8 has stated the principle of ignorance of law is no excuse.

2. Act alone does not amount to guilt. It must be accompanied by mens rea. (exception strict liability)

The principle "Act alone does not amount to guilt; it must be accompanied by mens rea" is a fundamental concept in criminal law. It means that in order to be guilty of a crime, a person must not only have committed a physical act (the actus reus), but they must also have had a guilty mind (mens rea) or criminal intent at the time of committing the act.

Key Elements:

- Actus Reus (the physical act): This refers to the actual conduct or the physical element of the crime. For example, in a theft, the act of taking someone's property without consent would be the actus reus.

- Mens Rea (the mental state): This refers to the mental state or intention of the person committing the act. For example, in theft, the person must have the intention (or knowledge) of stealing someone's property with the intent to deprive them of it permanently.

In many criminal cases, both actus reus and mens rea must be proven in order to convict someone of a crime. The mens rea shows that the person had the intent or recklessness to commit the act, not just that they accidentally or unintentionally did it.

Exception: Strict Liability Offenses

However, in some cases, strict liability offenses come into play. These are crimes where mens rea is not required for liability. In strict liability crimes, even if a person did not have the intent to commit the offense, they can still be found guilty as long as they committed the prohibited act (actus reus).

Strict liability crimes are typically less severe offenses, and they are often regulatory or administrative in nature. They are designed to encourage people to follow safety rules or regulations, even if they didn't intend to break the law.

For example:

- Traffic violations (like speeding) are often strict liability offenses. A person doesn't need to intend to break the speed limit; simply exceeding the limit can result in a fine or penalty.

- Selling alcohol to a minor: In some jurisdictions, even if the seller didn't know the buyer was underage, they could still be held liable.

In strict liability offenses, the law doesn't require proving that the person had a "guilty mind" (mens rea), only that they committed the act (actus reus).

3. Doctrine of double jeopardy

The Doctrine of Double Jeopardy is a legal principle that prevents an individual from being tried twice for the same offense. Once a person has been acquitted (found not guilty) or convicted (found guilty) of a crime, they cannot be prosecuted again for the same offense in the same jurisdiction. This doctrine serves as a safeguard against legal harassment and ensures finality in criminal proceedings. Muluki Criminal Code 2074 Sec 9 has established that no person shall be prosecuted in a court and punished again for the same offence. Constitution of Nepal 2072 Art 20(6) states that no person shall be tried and punished for the same offence in a court more than once.

Key Aspects of Double Jeopardy:

- Acquittal or Conviction: Once a person has been acquitted (found not guilty) or convicted (found guilty) by a court, they cannot be tried again for the same offense in the same court. This is the core of the double jeopardy protection.

- Same Offense: The offense for which the person has been acquitted or convicted must be the same in order for the double jeopardy rule to apply. If the person is tried for a different offense, even if related to the same incident, it would not violate the principle.

- Same Jurisdiction: Double jeopardy applies only within the same jurisdiction. In some legal systems, the principle may not apply if the offense is prosecuted in different jurisdictions. For example, someone could potentially be tried in both state and federal court for the same action, because these are considered separate legal systems.

Double Jeopardy Exists in:

- Finality: It ensures that once a person has been tried, either acquitted or convicted, the legal proceedings are considered final and cannot be repeatedly reexamined by the state.

- Protection from Abuse: It protects individuals from being harassed by the legal system through multiple trials for the same offense, which could be financially, emotionally, and mentally taxing.

- Fairness: The doctrine serves as a fundamental safeguard to prevent the state from using its resources to repeatedly pursue the same case against a person who has already been judged.

Exceptions to Double Jeopardy:

Doctrine of Double jeopardy doesn’t exist in some circumstances; exceptions are as follows:

- Appeals: In some legal systems, the prosecution can appeal an acquittal in certain cases, especially if there is new evidence or if there was an error in the legal process.

- Separate Jurisdictions: As mentioned earlier, someone could potentially be tried in both state and federal courts for the same act because these are considered separate legal systems.

- Mistrials: If a trial ends in a mistrial (for example, due to a hung jury), the defendant can be retried. A mistrial does not bar a second trial.

- New Evidence: In some jurisdictions, if new and substantial evidence emerges after an acquittal, the person could potentially be retried, although this is generally rare and subject to strict conditions.

- Civil vs. Criminal Cases: Double jeopardy only applies to criminal prosecutions. A person can be tried for the same act in both a criminal court and a civil court (for example, in cases of personal injury or wrongful death) because these are separate types of legal proceedings.

4. Criminal law has no retrospective effect

The principle that criminal law has no retrospective effect means that a person cannot be punished for an act that was not a crime at the time it was committed. In other words, a law cannot be applied to actions that occurred before the law was enacted. This principle is also known as the prohibition of ex post facto laws (Latin for "after the fact"). Muluki Criminal Code 2074 Sec 7 stated that no person shall be liable to punishment for doing an act not punished by law, nor shall a person be subjected to punishment which is heavier than the one prescribed by law in force when the offence was committed. The constitution of Nepal 2072, Art 20(4) has stated that no person shall be liable for punishment for an act which was not punishable by the law in force when the act was committed nor shall any person be subjected to a punishment greater than that prescribed by the law in force at the time of the commission of the offence.

Elements of this principle

- No Punishment for Past Acts: If an action was legal when performed, but later a law is passed making that action illegal, a person cannot be prosecuted for having done it before the law was enacted.

- No Harsher Penalties Retroactively: If a law increases the punishment for a crime, it cannot apply to crimes committed before the law was passed. A person must be punished according to the law that was in effect at the time of the offense.

- No Creation of New Crimes After the Fact: The government cannot criminalize an action after someone has already done it and then prosecute them for it.

5. Crime dies with criminal

The phrase "crime dies with the criminal" means that when a person accused or convicted of a crime passes away, the criminal prosecution or punishment against them is usually terminated. This principle is based on the idea that criminal liability is personal and does not transfer to heirs or family members.

Muluki Criminal Code 2074 Sec 133 mentions this principle.

Elements of this Principle:

- Criminal Proceedings End Upon Death

- If a person is on trial and dies before a verdict is reached, the case is generally dismissed, as the accused can no longer defend themselves.

- If a person has already been convicted but dies before serving their full sentence, their punishment typically ceases.

- Punishment Cannot Be Inherited

- Criminal liability does not transfer to the accused’s heirs, meaning their children or relatives cannot be held responsible for their crimes.

- Applies to Both Trial and Punishment

- If a person dies before being sentenced, the case is closed.

- If a person dies while serving a prison sentence, the punishment stops, as the justice system does not punish the deceased.

6. Information made in good faith does not create criminal liability.

This principle means that if a person provides information or makes a statement honestly and without malicious intent, they cannot be held criminally liable even if the information later turns out to be false or incorrect. The key element here is good faith, the person must have genuinely believed that the information was true or necessary to share. Muluki Criminal Code 2074, Sec 21 states that no information or communication of any matter made in good faith shall be considered to be an offence by reason of any harm to the person to whom it is made if it is made for the benefit of that person.

Elements for this Principle:

- Good Faith Requirement

- o The person must have acted with honest intention and without the intent to deceive, harm, or mislead others.

- No Criminal Intent (Mens Rea)

- Criminal liability generally requires mens rea (a guilty mind). If someone shares information believing it to be true, they do not have the criminal intent necessary for liability.

- Protection for Honest Mistakes

- If a person unknowingly provides incorrect information but did so with good intentions, they are not criminally liable.

The general principles of criminal liability establish the foundational legal doctrines that guide the prosecution and adjudication of criminal offenses. These principles ensure fairness, uphold justice, and balance the rights of individuals with the need for legal accountability. The principle that "ignorance of the law is no excuse" ensures that individuals remain responsible for understanding and following the law, while the requirement of both actus reus and mens rea in most offenses safeguards against wrongful convictions based solely on actions without criminal intent. Exceptions such as strict liability recognize the need for regulatory enforcement in certain cases.

Furthermore, doctrines like double jeopardy prevent individuals from being tried twice for the same offense, reinforcing the finality of judicial decisions and protecting against state overreach. Similarly, the prohibition against retrospective criminal laws ensures that individuals are not unjustly punished for actions that were not crimes at the time they were committed. The principle that "crime dies with the criminal" acknowledges that criminal liability is personal, while the protection of good faith statements from criminal liability encourages transparency and honesty.

These principles collectively uphold the integrity of the legal system, ensuring justice while protecting individual rights. By adhering to these doctrines, criminal law remains a fair and effective instrument of justice.

Disclaimer:

This article is intended solely for informational purposes and should not be interpreted as legal advice, advertisement, solicitation, or personal communication from the firm or its members. Neither the firm nor its members assume any responsibility for actions taken based on the information contained herein.